We recently got to sit down with Dr Jenny Neville, Reader in Early Medieval Literature in the Department of English, to hear more about her current work with Dr Megan Cavell (University of Birmingham) on early medieval poetic riddles. Funded by UK Research and Innovation, this research offers a glimpse into the early medieval world for researchers and members of the public, inspiring creative engagement through a website, curriculum resources, and even an escape room.

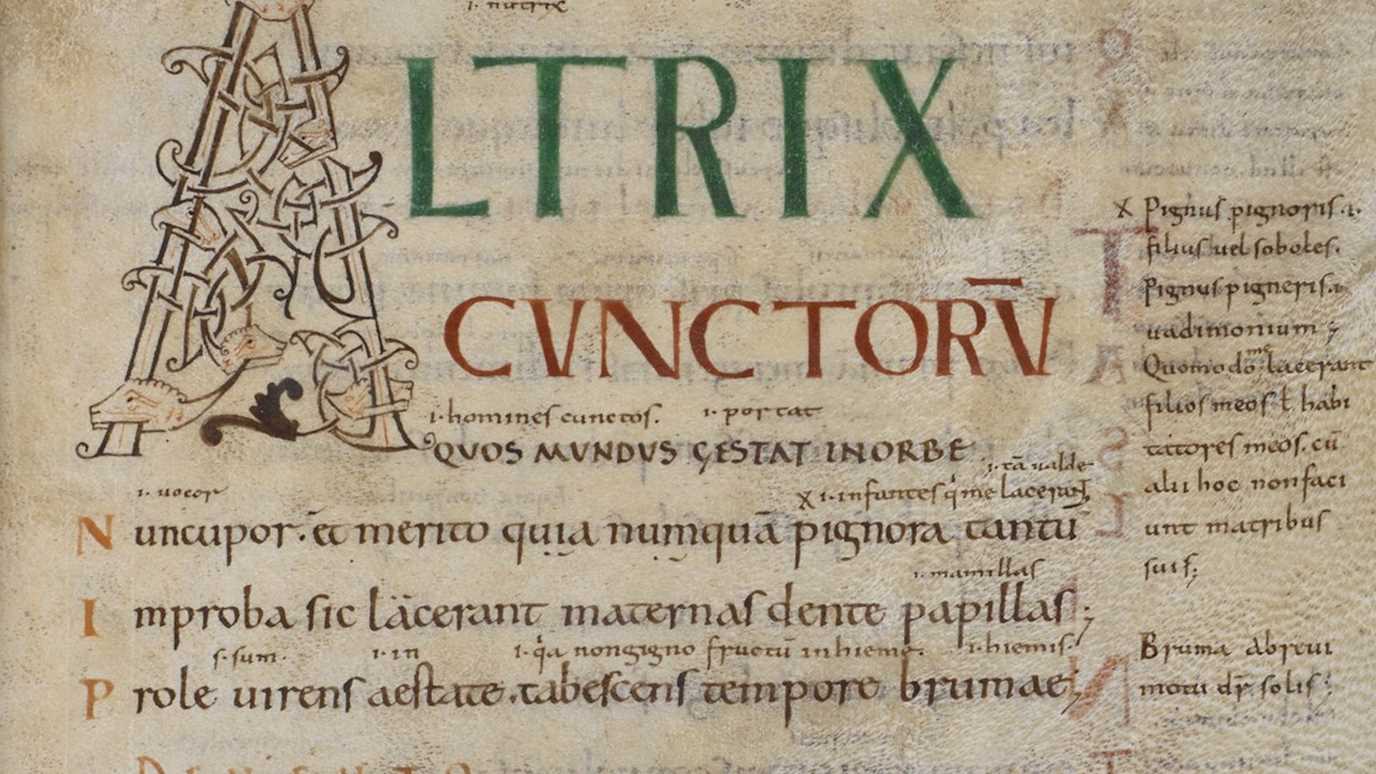

A photo of the opening page of Aldhelm's riddles, an early medieval manuscript.

The project builds on both Dr Neville and Dr Cavell’s extensive research, with Jenny’s latest book, Truth is Trickest: Enigmatic Tropes in the Exeter Book of Riddles, due to be published soon. Typically, the early medieval riddles which have been investigated are those written in Old English, but these commonly known riddles, Dr Neville explains, are the ‘tip of the iceberg only’. Numerous riddles were written and disseminated in Europe beyond the corpus which is well-known. These other riddles form part of the broader European tradition and offer important insight into networks and identities in the early medieval world. Key to this project is the group identity – or community – which these riddles convey.

Initially, Dr Neville and Dr Cavell planned to trace connections between myriad riddles across Europe – uncovering the contexts in which they were written and disseminated. The project then evolved to focus on the riddle collection of St Boniface. Boniface is not particularly well-known in England, although he was an Englishman by birth. Boniface travelled to Germany, as a missionary, to convert Germans and improve the church. He embarked upon his journey alone, though he was supported by a network of people back home in England, especially women. Exchanging letters and riddles with women back home in England, he fostered a community of support.

Dr Neville explains that identity is conveyed through these tricky pieces of writing. Exchanging riddles invited the recipient to a relationship with the writer by asking ‘What kind of person are you? I’m the kind who appreciates tricky poetry…and here is my challenge to you. Can you answer it?’ Riddles, therefore, offer commentary about early medieval community. As Dr Neville notes, ‘There is a conversation, a community of riddling going on’.

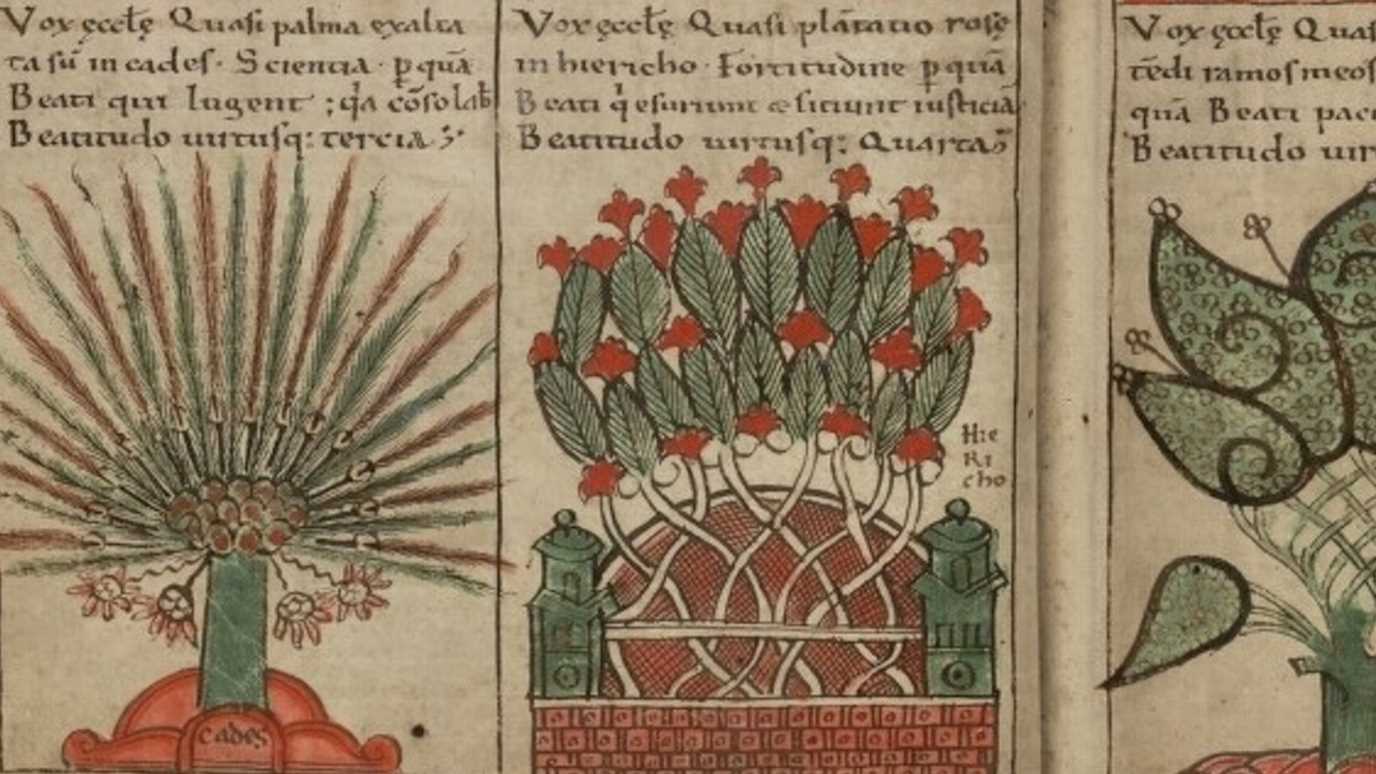

Early medieval riddles explored a variety of themes. They often unveiled daily life, focusing upon everyday items from the natural and domestic worlds. Scales, double broilers, and ploughs feature in many riddles. Riddles were also used to convey abstract concepts such as pride and ignorance. Whilst riddles have often been associated with educational purposes – teaching children to learn Latin – the riddles curated by Boniface were theological and philosophical, even if they are sometimes accused of being derivative, borrowing clauses from earlier riddles. Dr Neville suggests this was part of the communal relationship being created; there was an expectation that the writers and their recipients already knew about these riddles and will make intellectual connections when they read them. A community was forged in these exchanges, a sort of family, suggests Dr Neville: ‘It’s this idea of a different kind of family being built up through texts over a distance.’

Whilst steeped in early medieval history, these riddles can also comment upon contemporary issues. Recent conversations about Brexit often came back to the idea about England being an island, separate and independent. These riddles, however, demonstrate how early medieval England was a community, in conversation with people from other parts of the world, such as Europe and Africa. The riddles contribute to conversations about racism, showing an alternative world to that which has recently focused on the masculinist racist ideas promoted using Beowulf. Riddles evince a community which transcended racial boundaries. The riddles also comment upon gender, as evidence uncovers women who though not viewed equally were not absent either. These women were literate, able to read and write Latin poetry.

Dr Neville and Dr Cavell have ambitious plans for the resources to be developed by this project. The website will offer visitors original texts, translations, commentaries, and bibliographies for myriad riddles investigated in this project. In association with their project partners (National Trust: Sutton Hoo and Birmingham Museums Trust, among others) the significance of these riddles will be shared through curriculum resources in schools. A medieval library-themedRiddlequest, an ‘escape room’ to be hosted in autumn 2022 at NT:SH (aimed at secondary school pupils and adults), is also being curated usinguses riddles based on those discovered explored in the project. The overall aim of this project is to enrich public experience of the Middle Ages. As Jenny explains:

‘Any kind of research that shows the Middle Ages is not just knights on horseback is valuable… this project shatters this single image of the Middle Ages and shows how rich and interesting it can be.’

To offer a taste of her research, Jenny concludes by offering an example of an Early Medieval riddle with a brief note of commentary.

Exeter Book Riddle 5: The Anhaga (‘Loner’)

Ic eom anhaga iserne wund,

bille gebennad, beadoweorca sæd,

ecgum werig. Oft ic wig seo,

frecne feohtan. Frofre ne wene,

þæt me geoc cyme guðgewinnes,

ær ic mid ældum eal forwurðe,

ac mec hnossiað homera lafe,

heardecg heoroscearp, hondweorc smiþa,

bitað in burgum; ic abidan sceal

laþran gemotes. Næfre læcecynn

on folcstede findan meahte,

þara þe mid wyrtum wunde gehælde,

ac me ecga dolg eacen weorðað

þurh deaðslege dagum ond nihtum.

I am a loner, wounded by iron, injured by blade, sated with battle-work, weary of swords. I often see a dangerous battle fought. I do not expect comfort—that rescue from war-struggle will come to me before I entirely perish among men. Instead, the leavings of hammers, the handiwork of smiths, hard-edged and battle sharp, will bite me within the enclosures. I must await a harder meeting. In the settlement I could never find (one of) the race of doctors, (one of those) who might heal (my) wounds with herbs. Instead day and night the scars from swords become greater with (every) deadly stroke.

The first and most important thing to remember is that there are no solutions for this riddle in the manuscript, so we can never be certain that any solution is correct. Most people solve this riddle as ‘shield’ and see it as just another story about the world of warriors in battle, but this riddle is not about the glorious hero who triumphs in war; it is about the one who loses. And so, even if you solve it as ‘shield’, it provides a perspective on war very different from the martial enthusiasm most expect from the Middle Ages. I do not believe that this is a shield, however. Shields are not loners; when you use a shield, there are other shields in play. Shields are used on battlefields, not inside settlements (and certainly not indoors). And shields are not used both day and night, because, despite what Tolkien tells us, medieval battles started at dawn and stopped when the sun went down, because you simply cannot fight in the dark. I have a list of six other possible solutions, but my favourite one is probably ‘chopping board’. Like a shield, a chopping board is constantly attacked by blades, but the ‘battle’ is a domestic one, pursued (gasp!) by women, who cut up the herbs that might elsewhere be the ingredients for a medicinal salve but here are merely seasoning for dinner. The tragic, heroic language in this text thus adorns a very different space. Whether that space really is the kitchen rather than the battlefield, the correct response to this text is an argument.

Dr Jenny Neville was interviewed by Angela Platt, a PhD student in History and an Engaged Humanities Officer.