James S. Williams is Professor of Modern French Literature and Film at Royal Holloway. His 2019 monograph, Ethics and Aesthetics of African Cinema: The Politics of Beauty was honoured with the 2020 R. Gapper Prize for ‘the best book in the field of French studies, published for the first time in the previous calendar year, by a scholar based in an institution of higher education in the United Kingdom or Ireland'. This is the first time a book exclusively on film has been recognised in this way by the Society

In Afropolitan flux: Félicité (Véra Tshanda Beya) being transported through the working-class districts of Kinshasa in Félicité (2017), dir. Alain Gomis.

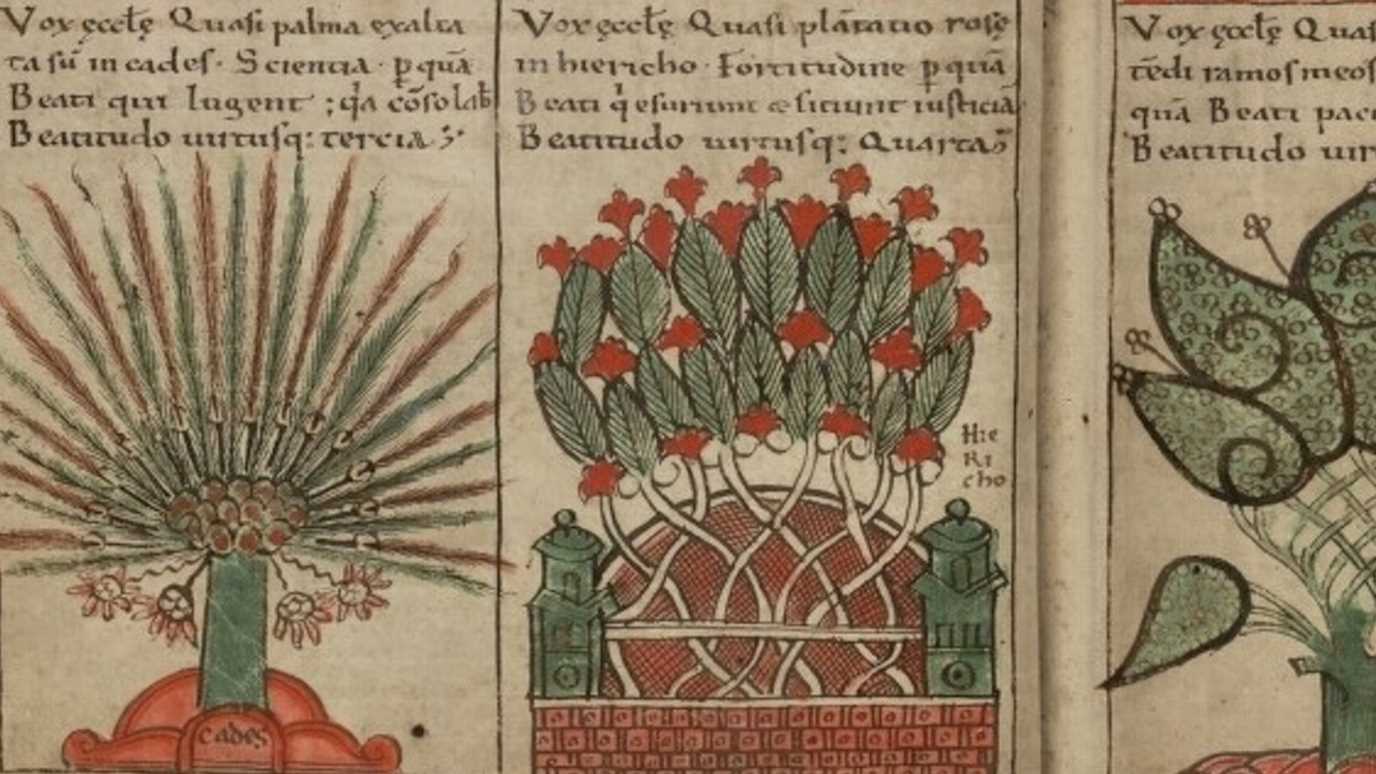

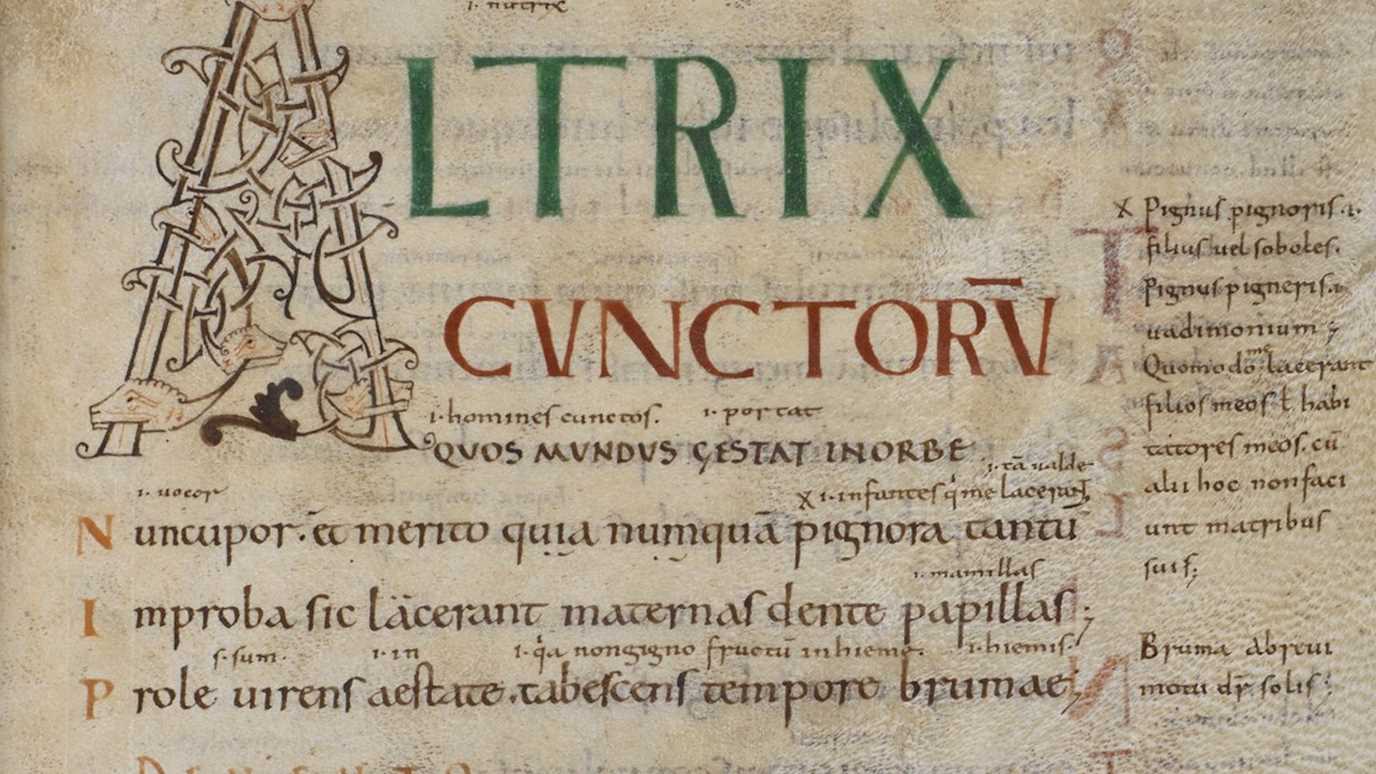

Williams’ background is in French and Francophone cinema. He was drawn into the world of millennial sub-Saharan African cinema by seeing Mauritanian director Abderrahmane Sissako’s 2006 film Bamako, about a mock trial of the World Bank that takes place in a courtyard in a working-class area of the capital of Mali. While African cinema in the immediate postcolonial period was largely allegorical, Bamako did something entirely different as it is not strictly allegorical. Rather, it uses a powerful recurring visual metaphor of local batik cloth (endangered by globalisation) to convey a thousand messages, some obvious and some very subtle indeed. ‘A lot of the energy I had for this project comes from trying to work out what is happening in Bamako’, Williams says.

Born in Zambia, Williams has travelled in central and west Africa, spending time in the Senegalese capital Dakar. ‘It is important to me to have spent time there,’ says Williams. Spending time immersed in the culture he is studying means that his scholarship comes from empirical experience – what he saw, heard, and felt in Africa – not just theory. Travel to Mali and Burkina Faso, where African cinema has its institutional base, is presently too dangerous, but Williams hopes eventually to travel there as well.

Since the publication of Ethics and Aesthetics of African Cinema, Williams has turned to looking at what European filmmakers say about migration from Africa – especially about those migrants fleeing not war or poverty, but persecution in Africa because of their sexuality. In 2021, Routledge released a collection of essays edited by Williams, entitled Queering the Migrant in Contemporary European Cinema. His own contributions looked at (queer) French filmmakers who have (and have not) engaged with the idea of a non-European ‘other’ who arrives in Europe, and British and Finnish queer cinema (including Mikko Makela’s 2017 film about a queer Syrian migrant, A Moment in the Reeds). His aim was to give a comparative view and engage deeply with the topic, exploring the problems for European filmmakers who try to do justice to the topic of African migration, but fall into certain traps. Other contributions come from different cultures and backgrounds across Europe. Williams’ interview with the postcolonial theorist Sudeep Dasgupta, who is also a programmer at Amsterdam’s annual International Queer & Migrant Film Festival, rounds off the volume.

African filmmaking is evolving, with newer films doing something very different from the first postcolonial African cinema of the 1960s and 70s. Evolving beyond the work of noted Senegalese auteur Ousmane Sembene, the ‘father of African film’, new filmmakers are exploring thematic zones of violence, terrorism, language and non-communication, intimacy, gender, migration, and the city as ‘afropolis’. Intervening polemically in the highly conservative field of African film studies, Williams’ work engages with recent films in all their rich textural detail for the first time, rather than attempting to derive a simple message from them. He has argued that scholarship needs to move beyond the traditional framework used by film scholars to interpret the work of filmmakers like Sembene. This ‘post-baobab thinking’ (moving beyond the visual metaphor of the baobab tree and the ‘wax and gold’ method used extensively in immediate postcolonial cinema) is ‘very sensory, trying to trace and understand, but also to open up to new types of aesthetic, beyond the original suspicion of beauty in Sembene’s work’, in which beauty was seen as ‘Western’, ‘tainted’, or ‘exoticised’.

Williams’ latest work is on Black British and African American cinema, addressing the questions of racism brought to the fore by Black Lives Matter. ‘I see cinema as having a key role in engaging with these questions,’ says Williams. ‘Cinema can engage with questions directly and give us something. That’s what interests me the most: cinema’s ability not just at a visual level, but also with sound, to engage with the current historic, political, and social period.’ Especially important to Williams is to study the interaction of film with literature. He uses his dual background in literature and cinema to work with theorists and writers on negritude and Black lived experience and postcolonial experience. He is also working on a critical biography of Frantz Fanon, a revolutionary, writer, theorist, and playwright from the former French colony of Martinique.

Professor James Williams was interviewed by Charlotte Gauthier, a PhD student in History and Engaged Humanities Officer.