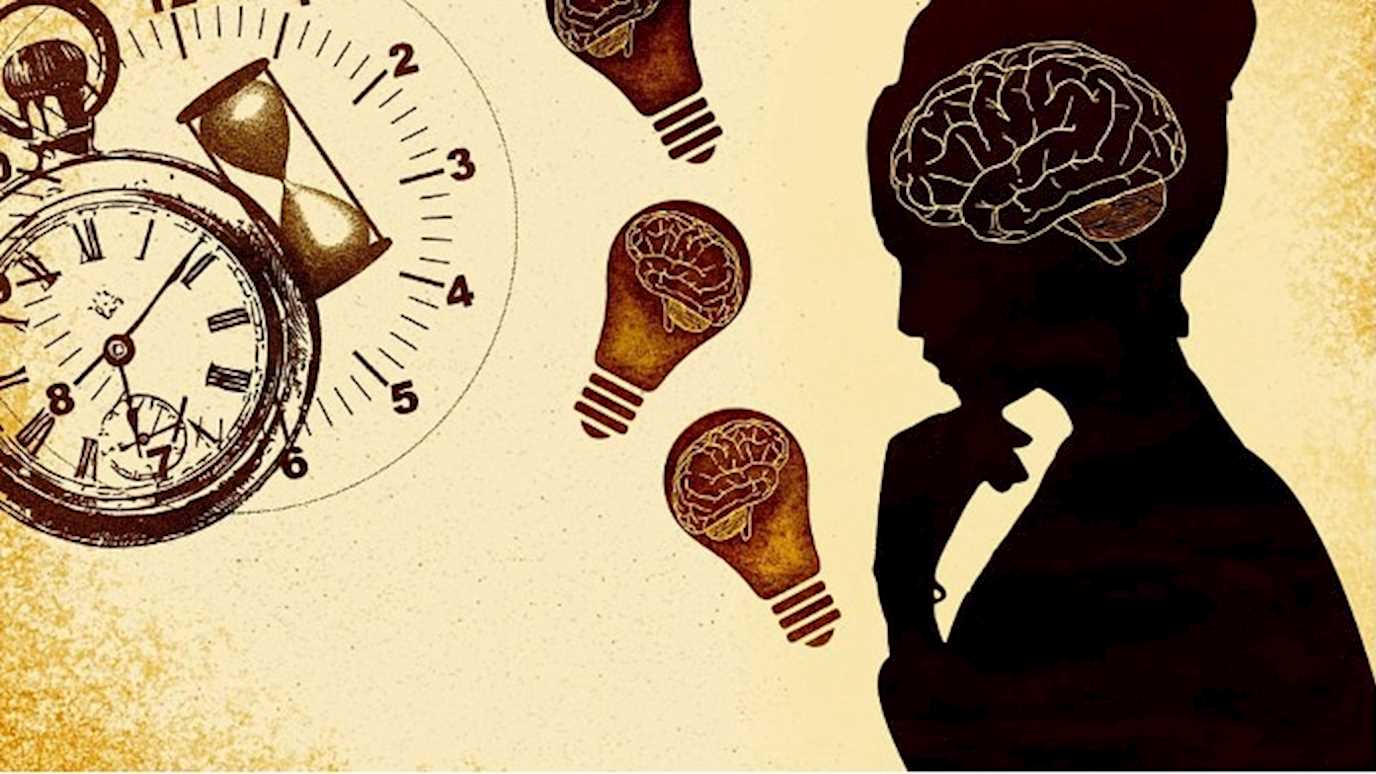

Researchers from Royal Holloway, University of London, have published a new study in Behavioural Brain Research that shows that imagining an action requires executive resources located in a specific brain area called the Dorsolateral Prefrontal Cortex, in support of a new theory, the Motor-Cognitive model of motor imagery. These findings, and the Motor-Cognitive model, pose the first serious challenge to the decades-old theory known as “Functional Equivalence”, which contends that motor imagery uses the same brain areas as physical actions.

Adults are generally quite efficient at imagining their own actions without moving. Most of the time, physical and imagined actions have a similar duration, which is why it has long been thought that both were functionally equivalent and involved the same brain processes.

The Motor-Cognitive model, in contrast, argues that motor imagery uniquely uses executive resources. Using Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation, researchers disrupted the functioning of the Dorsolateral Prefrontal Cortex, where executive resources reside, and observed the consequences it had on performance. Participants were slower at imagining an action after receiving TMS compared to those who did not; physical actions were not impacted, highlighting the specific involvement of the DLPFC in motor imagery.

Dr Marie Martel said: “Our results are interesting because they show that executive resources are crucial during motor imagery only and that motor imagery is thus not functionally equivalent to physical actions. For decades everyone has been using an overly simplified model, it is now time to consider a new theory of motor imagery.”

Dr Scott Glover said: “The implications of this work for not only understanding motor imagery but also optimising its application to skill training and rehabilitation are enormous. Our sense is that applying the Motor-Cognitive model to these pursuits will involve trainers and therapists considering the important role of executive functions in motor imagery, and updating their techniques to take advantage.”

“TMS over dorsolateral prefrontal cortex affects the timing of motor imagery but not overt action: Further support for the motor-cognitive model” was carried out by Dr Marie Martel, post-doctoral researcher, and Dr Scott Glover, senior lecturer, both part of the Department of Psychology.