Professor Kiernan Ryan on Shakespearean Tragedy.

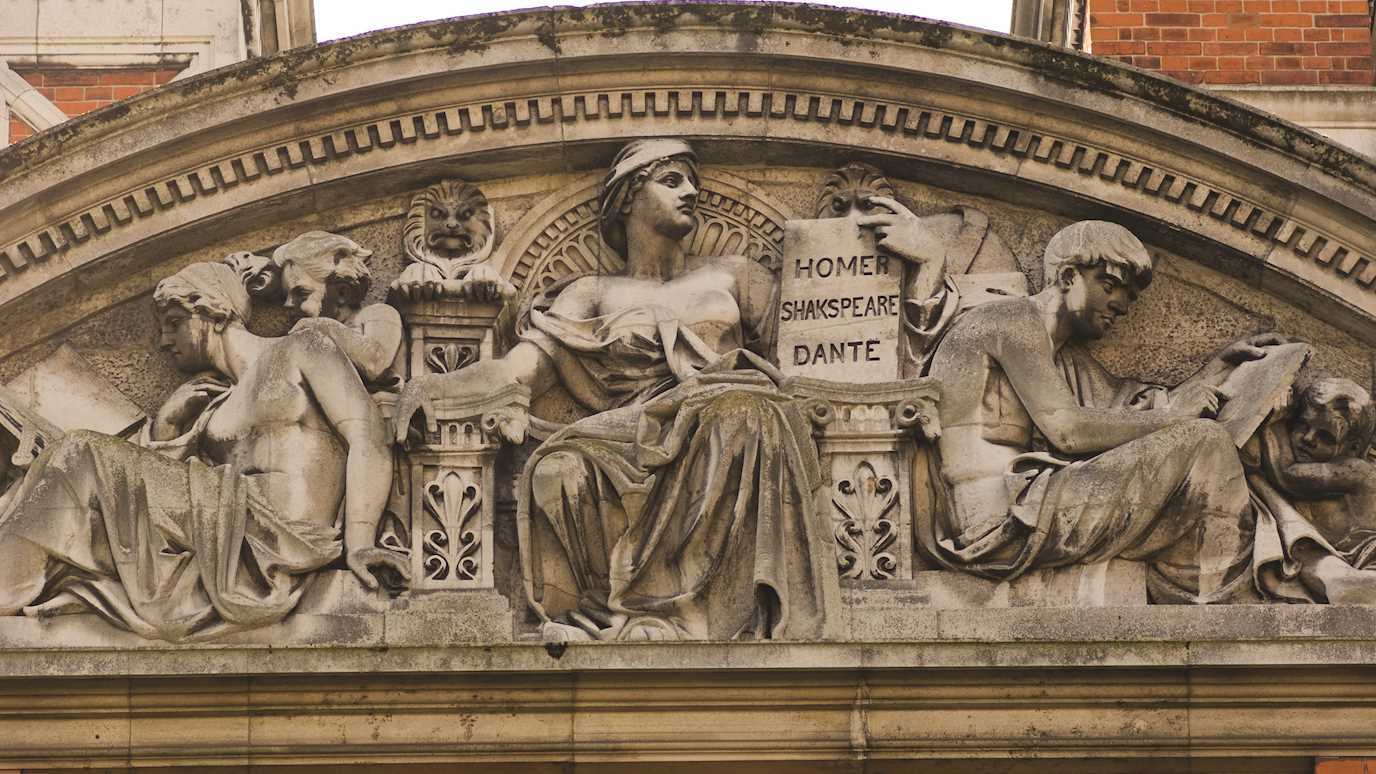

The English Department at Royal Holloway is home to several renowned Shakespeare scholars including Dr Deana Rankin and Dr Harry Newman. You can study Shakespeare generally as part of the English Literature MA, and with particular focuses on the module ‘King Lear and The Tempest: Critical Debate and Creative Response’.

Key Points

- The main plays we usually have in mind when discussing Shakespeare’s tragedies are Titus Andronicus, Romeo and Juliet, Julius Caesar, Hamlet, Othello, King Lear, Macbeth, Antony and Cleopatra, and Coriolanus. There’s a lot to be said for treating each of the tragedies first and foremost as a unique work of dramatic art. But that doesn’t preclude there being something distinctively Shakespearean about their tragic vision that sets them apart from other kinds of tragedy.

- The key feature they have in common is perhaps best illustrated by Romeo and Juliet. What makes their fate tragic in the Shakespearean sense is that they live at a time when a genuinely mutual love like theirs cannot survive, because it belongs to a future women and men are still striving to create. Their tragedy is to be fated to die in a hostile, alien reality, stranded far from the transfigured world whose possibility they foreshadow.

- It’s not hard to see how the same holds true of the protagonists of Shakespeare’s other great tragedies of doomed love, Othello and Antony and Cleopatra. The heart-breaking conflict between what human beings could be and what their time and place condemn them to become couldn’t be clearer in these plays. Shakespeare’s creation in them of characters who can’t come to terms with their world reveals the capacity of human beings, then and now, to be radically different from the way their world expects them to be.

- With that in mind, it’s easier to see what the other tragedies have in common with the love tragedies – what’s distinctively Shakespearean about them too. Every one of their tragic protagonists is doomed by being cast in the wrong role in the wrong place in the wrong time. Every one of them becomes a stranger in a world where they’d once felt at home, and a stranger to the person they thought they were. And in the process every one of them reveals the potential to be another kind of person in a truly civilized world, which they will tragically never live to see.

- That the tragedies are rooted in the age of Shakespeare, and that they can’t be fully understood without knowledge of the world and the language they were written in, goes without saying. But no critical account or production can do justice to Shakespeare’s tragedies, if it’s not also attuned to the ways in which they were ahead of his time and remain ahead of our time too.

Further Reading

Kiernan Ryan, Shakespeare, third edition, Chapter 3: ‘Shakespearean Tragedy: The Subversive Imagination’, especially pp. 72-82 on ‘Romeo and Juliet: The Murdering Word’.

A. C. Bradley, Shakespearean Tragedy, third edition (Houndmills: Macmillan, 1992), Lecture I: ‘The Substance of Shakespearean Tragedy’.

Adrian Poole, Tragedy: A Very Short Introduction (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005).

Claire McEachern (ed.), The Cambridge Companion to Shakespearean Tragedy, second edition (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2013), especially Colin Burrow, ‘What is a Shakespearean Tragedy?’ and Paul Kottman, ‘Why Think about Shakespearean Tragedy Today?’

Janette Dillon, The Cambridge Introduction to Shakespeare’s Tragedies (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2007).