Dr Christie Carson on Hamlet.

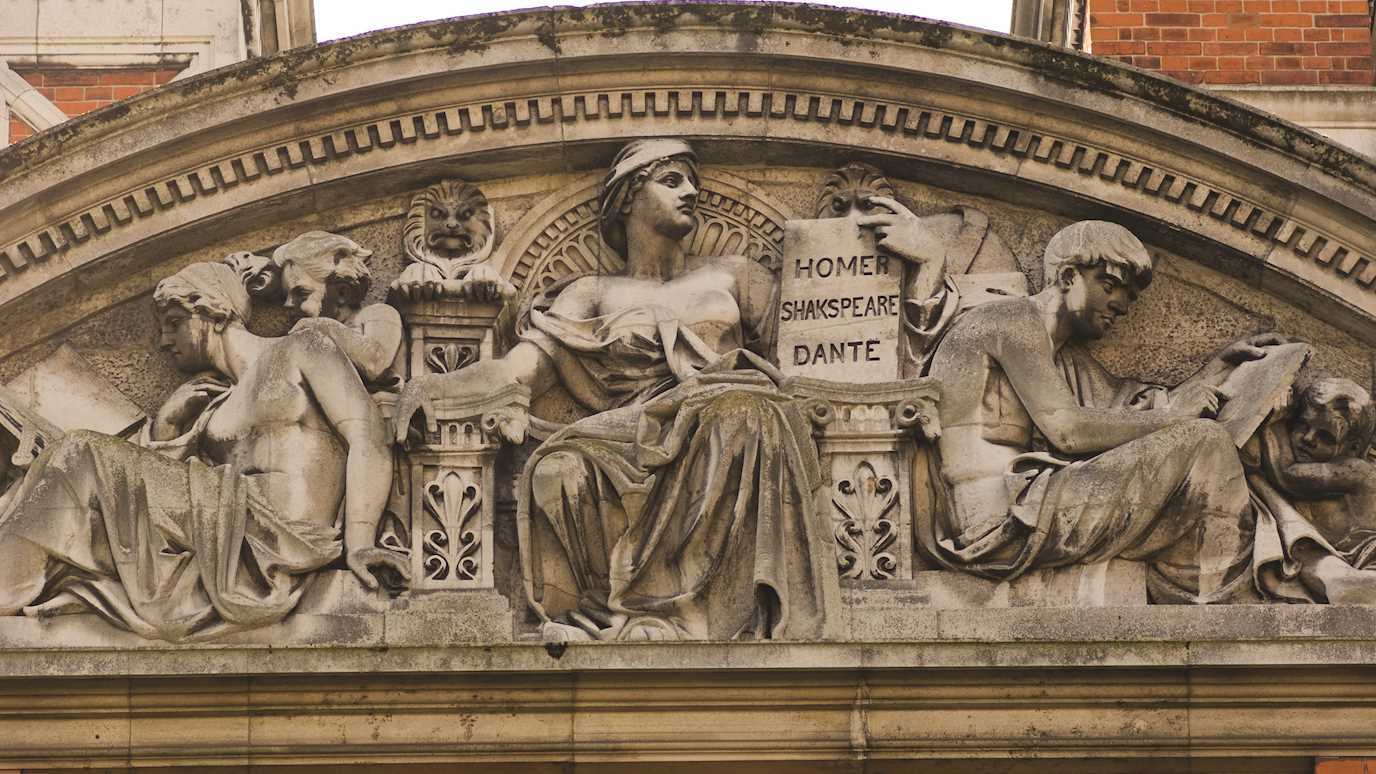

The English Department at Royal Holloway is home to several renowned Shakespeare scholars including Dr Harry Newman and Dr Deana Rankin. You can study Shakespeare generally as part of the English Literature MA, and with particular focuses on the module ‘King Lear and The Tempest: Critical Debate and Creative Response’.

Professor Kiernan Ryan on Hamlet

Key Points (Professor Kiernan Ryan)

- In Hamlet, Shakespeare sabotages the conventions of revenge tragedy by creating a hero who finds himself, to his own bewilderment, unable to fulfil his duty to avenge his murdered father without delay. When he does finally avenge him at the end of Act 5, he does so on the spur of the moment, at the cost of his life, and too late to prevent all the deaths that need not have occurred if he had avenged him sooner.

- On the face of it, the main cause of the tragedy is Hamlet’s inexplicable reluctance to kill his father’s murderer, which compels him to procrastinate until circumstances force his hand. In this widely accepted view of the play, Hamlet’s compulsion to postpone what he has sworn to do is his ‘tragic flaw’ and the fundamental problem the play poses is: Why does Hamlet delay?

- But what if we turn this view of the play on its head? What if Hamlet’s tormented aversion to performing the role of avenging prince reflects a justified rejection of a whole way of life, whose injustice and corruption he now finds intolerable? In that case his tragedy is being forced to play a pointless part in a society from which he feels utterly alienated. It’s the time that’s ‘out of joint’ (1.5.188), not Hamlet. And being out of sync with his time is what makes him a hero ahead of his time.

- Viewed from this standpoint, the problem the play appears to pose - Why does Hamlet delay? – disappears along with the notion that his compulsion to delay constitutes his ‘tragic flaw’. Shakespeare refuses to reduce the cause of the tragedy to ‘the stamp of one defect’ (1.4.31) in Hamlet, because that would mean pinning the blame on the protagonist alone, instead of calling into question the society that trapped him in such an impossible predicament in the first place.

- His predicament is impossible because, if he fails to kill his father’s murderer, his father goes unavenged and his killer escapes justice; but if he succeeds in killing him, he becomes complicit with the hierarchical society that fostered the regicide for which he seeks revenge. So, with no satisfactory course of action open to him, paralysed by the futility of the revenge he is obliged to seek, Hamlet stalls and prevaricates, playing for time until he kills Claudius on the spur of the moment. Hamlet does avenge his father in the end. But not before his revolt against his role has revealed Shakespeare’s time as a time that only the ‘fine revolution’ (5.1.90) Hamlet glimpses in the graveyard could set right.

Key Points (Dr Christie Carson)

1. Isolation and Alienation

2. The other family relationships in the play

3. Context: where is Shakespeare's Denmark?

4. The ending: who knows what?

5. The textual complexities of the play: the several possible Hamlets

Key quotations

Hamlet:

O that this too, too solid flesh would melt,

Thaw and resolve itself into a dew,

Or that the Everlasting had not fixed

His canon ’gainst self-slaughter. O God, God,

How weary, stale, flat and unprofitable

Seem to me all the uses of this world! (1.2.129-34)

Hamlet:

The time is out of joint; O cursed spite

That ever I was born to set it right. (2.1.186-7)

Hamlet:

Ay, sir, to be honest as this world goes is to be one man picked out of ten thousand. (2.2.175-6)

Hamlet:

Your fat king and your lean beggar is but variable service, two dishes but to one table. . . . A man may fish with the worm that hath eat of a king and eat of the fish that hath fed of that worm.

King:

What dost thou mean by this?

Hamlet:

Nothing but to show you how a king may go a progress through the guts of a beggar. (4.3.23-4, 26-30)

Hamlet:

I do not know

Why yet I live to say this thing’s to do,

Sith I have cause and will and strength and means

To do’t. (4.4.42-5)

Hamlet:

And now my Lady Worm’s – chapless and knocked about the

mazzard with a sexton’s spade. Here’s fine revolution if we had

the trick to see’t. (5.1.83-6)

Further Reading

T.S. Eliot, ‘Hamlet’, in Selected Essays (London: Faber & Faber, 1951), pp. 141-6.

Harold Bloom, Hamlet: Poem Unlimited (Edinburgh: Canongate, 2003).

René Girard, ‘Hamlet’s Dull Revenge’, in A Theater of Envy: William Shakespeare (New York: Oxford University Press, 1991), pp. 256-70.

A.C. Bradley, Shakespearean Tragedy, 3rd edn (Houndmills: Macmillan, 1992), ‘Lecture III: Shakespeare’s Tragic Period: Hamlet’.

Martin Coyle (ed.), Hamlet: Contemporary Critical Essays (Houndmills: Macmillan, 1992).

Ann Thompson and Neil Taylor (eds), Hamlet: A Critical Reader (London: Bloomsbury, 2016).

Christie Carson and Farah Karim-Cooper (eds), Shakespeare's Globe: A Theatrical Experiment (Cambridge: CUP, 2008)