Professor Judith Hawley on Mary Shelley's Frankenstein

Key points

- The form of the novel:

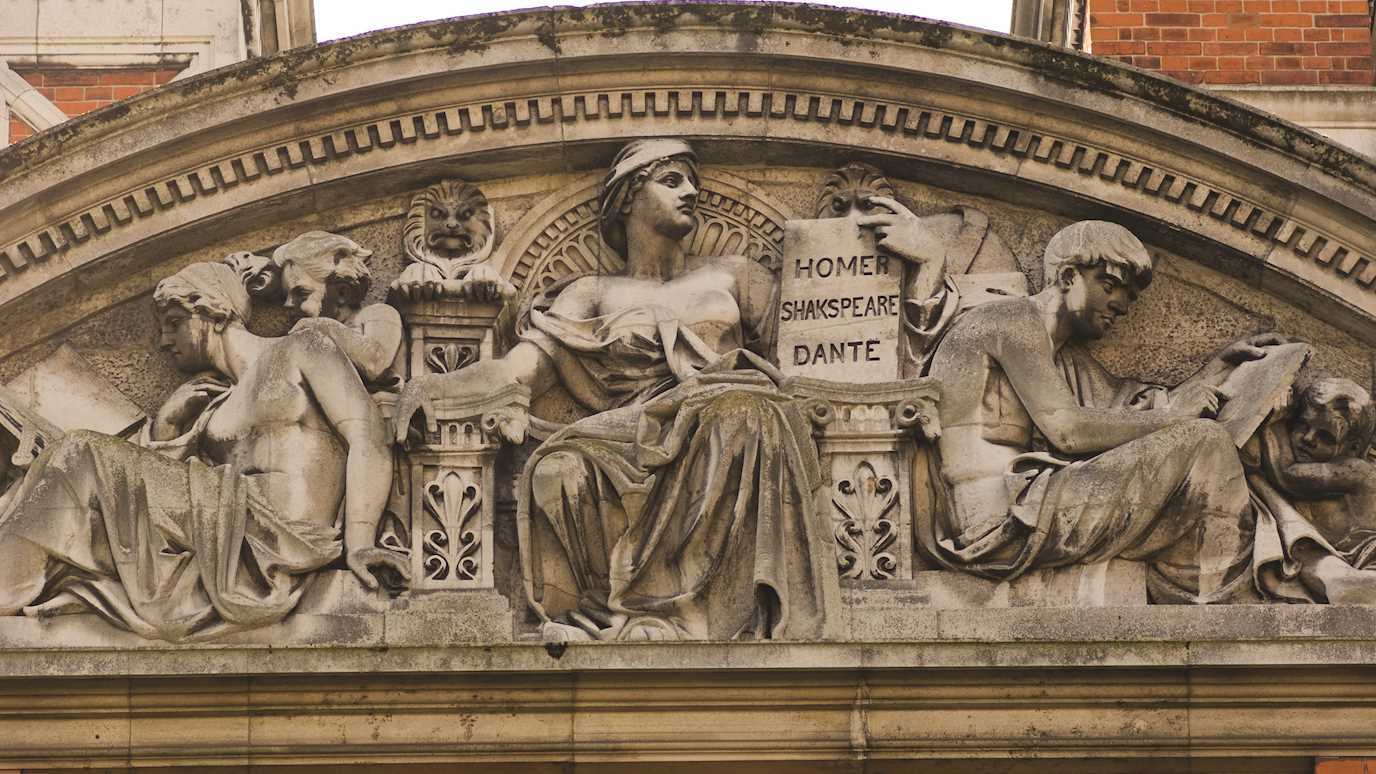

Shelley constructed a complex form for her narrative. The novel opens with Captain Walton’s letters to his sister, then shifts to Frankenstein’s account of his life. Inside his narrative is the creature’s account of his life. We then return to Frankenstein before the story is re-enclosed in Walton’s letters. The creature breaks through into the narrative frame. There are different ways of describing and visualising this form: we can think of it like a Russian doll (babushka), Chinese boxes, an onion, a series of frames or of mirrors … Why do you think Shelley embodied her story in this complex form? - The making of the monster:

Compare how the creation of the creature is depicted in films and popular literature with the descriptions Mary Shelley actually gives in her novel. In the first edition (published 1818), she says very little about how Frankenstein creates life. In the revised edition (1831) she adds a preface detailing her dream of creation, but still there are very few details in the text itself (see 1818 ed., vol. I, chapter III; 1831 ed., chapter iv). Compare this with, for example, the films directed by James Whale (1931) and Kenneth Branagh (1994). Popular reworkings of the story emphasise the dangers of science; Shelley focusses on how the creature is transformed into a monster by the way people treat him.

Quotations

- Oxford English Dictionary, s.v. ‘Monster’:

[Professor Judith Hawley's summary of the etymology: The word is derived from an old French word meaning ‘prodigy, marvel’, which itself is derived from the classical Latin mōnstrum portent, prodigy – a monster, then, can be seen as a warning.]

1.a. Originally: a mythical creature which is part animal and part human, or combines elements of two or more animal forms, and is frequently of great size and ferocious appearance. Later, more generally: any imaginary creature that is large, ugly, and frightening.

2. Something extraordinary or unnatural; an amazing event or occurrence; a prodigy, a marvel. Obsolete.

3. a. A malformed animal or plant; (Med.) a fetus, neonate, or individual with a gross congenital malformation, usually of a degree incompatible with life.

4. a. A creature of huge size.

5. A person of repulsively unnatural character, or exhibiting such extreme cruelty or wickedness as to appear inhuman; a monstrous example of evil, a vice, etc.

6. general. An ugly or deformed person, animal, or thing.

- ‘Frankenstein tends to employ devices to undermine the illusion, to draw attention to its own textuality. It refuses a single point of view, however complex and comprehensive and instead brings multiple points of view into unresolved collision or contradiction as Victor’s representation of the monster and the monster’s self-representation are at odds. As responsive readers of the text, then we should seek not the unity of the work, but the multiplicity and diversity of its possible meanings , its incompleteness, the omissions which it displays but cannot describe, and above all its contradictions. In its absences, and in the collisions between its divergent meanings, the text … contains within itself the critique of its own values.’ (Catherine Belsey, Critical Practice (NY: New Accents, 1980), p. 92)

Suggested passages

Nature Vs. Nurture:

One of the big themes Shelley analyses in her novel is the question of whether our birth or our experience makes us the way we are. This question is familiar as the nature vs. nurture debate and could lead into a discussion of the relative importance of DNA and social environment. Here are some of the key moments where these questions are explored: [check edition]

- Volume I, chapter ii:

Analyse Frankenstein’s description of his childhood. What do you think are the positive elements? Are there any signs of the problems that ensue? - Volume II, chapter iii:

Analyse the creature’s description of his first perceptions. What do they suggest about how individuals develop and engage with the world? - Compare Volume II, chapters vi and vii:

Analyse the creature’s description of his education. How much does he learn from people and how much from books?

Myth and interpretation:

Frankenstein derives partly from myths (such as that of Prometheus Plasticans or the creation as narrated in Genesis and Milton’s Paradise Lost). It has also become something of a myth itself. One feature of myth is that it is mutable, adaptable, alive, subject to interpretation. Here are some suggestions for ways of exploring this mutability:

- Analyse the representation and significance of Prometheus and Paradise Lost in Frankenstein.

- Resist myth-making by drawing on rationalism. Imagine that instead of pursuing him through the icy wastes, the creature decides to pursue Frankenstein through the courts and sues him for negligence, malpractice and emotional and physical distress. Mount the case that could be made on both sides.

- Within the novel itself and over the years, the creature has been subject to numerous interpretations. Here are some of the things the creature has been said to represent:

- The dangers of science

- The dangers of a world where women are marginalised

- The rise of the proletariat and the fear of revolution

- The vulnerability of a baby

- The dark double of Frankenstein himself

- A social outcast

- Evil

- Ambition – both that of the scientist and the imaginative creator

- A mother’s fears about what might become of her child

Further reading

- Melissa Bloom Bissonette, ‘Teaching the Monster: Frankenstein and Critical Thinking’, College Literature 37 (2010), pp. 106-120.

This article argues that students too readily associate Mary Shelley’s creature with cartoon monsters. Similarly, they can take a cartoonish attitude to the issues raised by the novel, reducing it to ‘either-or, straw-man terms’ of is the monster good or bad? Bissonette encourages us to foster more critical thinking by learning from Bertolt Brecht’s idea of alienation and critical distance. Resorting to sympathy for the creature, readers can sidestep analysis. If we keep the monstrosity of the monster in mind – his hideous appearance and his unnatural construction – we can appreciate how disruptive he is of our normal categories of good and evil, child and man, human and inhuman. She suggests various ways of promoting critical engagement with the novel such as reading a critical article or watching James Whale’s 1931 film before they read the book. She also uses a highly structured on-line discussion board to foster genuine interaction between students (so they are not just looking for approval of their points from the teacher) and leading students to revise their first thoughts in the light of later discoveries.

- Anna E. Clark, ‘Frankenstein; or, the Modern Protagonist’, Essays in Literary History Essays in Literary History 81 (2014):https://muse.jhu.edu/journals/elh/v081/81.1.clark.html

‘While readings of Mary Shelley's Frankenstein often consider the creature's thematic centrality and sympathetic appeal, I argue that the creature's exceptional status is due largely to his prowess as a narrator of other characters' points of view. All three of Frankenstein's first-person narrators present characters' biographies and focalized perspectives in their narrative frames, yet it is only the creature whose sustains an intimate, internally focalized engagement with another character's interiority. Frankenstein's interest in this comparative identification is indicative of a larger approach to characterization that I call protagonism, a term that describes novels' impulse to distribute the kinds of deep interiority and intimate identification we often associate with one or two privileged heroes among many textually and thematically marginalized figures.’

- Jerrold E. Hogle, ed., The Cambridge Companion Gothic Fiction (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2012). Available in print and as eBook.

Fourteen world-class experts on the Gothic provide thorough accounts of this haunting-to-horrifying genre from the 1760s to the end of the twentieth century. Essays explore the connections of Gothic fictions to political and industrial revolutions, the realistic novel, the theater, Romantic and post-Romantic poetry, nationalism and racism from Europe to America, colonized and post-colonial populations, the rise of film, the struggles between "high" and "popular" culture, and changing attitudes towards human identity, life and death, sanity and madness. The volume also includes a chronology and guides to further reading.

- Harriet Hustis, ‘Responsible Creativity and the "Modernity" of Mary Shelley's Prometheus’, Studies in English Literature 1500-1900 43 (2003), 845-58.

This article analyses how Mary Shelley's Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus reconfigures, decontextualizes, and thus ‘modernizes’ the myth of Prometheus. It argues that by focusing on the issues of paternal negligence and the need for responsible creativity, Shelley's novel deconstructs the story of Prometheus as a masculinist narrative of patriarchal authority. It concludes that an examination of the ‘modernity’ of Shelley's Prometheus myth has an impact not only on interpretations of Frankenstein itself, but also on the function of the novel's 1831 preface.

- Ronald Paulson, 'Gothic Fiction and the French Revolution', English Literary History 48 ELH (1981), 532-54.

Paulson argues that the Gothic ‘served as a metaphor with which some in England tried to come to terms with what was happening across the Channel in the 1790s.’ The image of the castle-prison, the sensitive girl oppressed by patriarchal forces, the satanic oppressor, the destruction of the castle by an angry mob – all of these could be ways of dramatizing the tension between celebrating the overthrow of tyranny and fearing a take-over by the dark forces it unleashes. His reading is detailed and nuanced and points out that the Gothic – a genre that pre- and post-dates the fall of the Bastille in 1789 – can be reduced to this formula, but this is the central claim of the argument. Of Frankenstein, he argues, it ‘was to some extent a retrospect on the whole process [from 1789] through Waterloo, with the Enlightenment-created monster leaving behind its wake of terror and destruction across France and Europe, partly because it had been disowned and misunderstood and partly because it was created unnaturally by reason rather than love.’ The writings of her mother, Mary Wollstonecraft, on the topic of the French Revolution, were an important influence on Shelley. Wollstonecraft argued that the Terrors perpetrated by the revolutionaries were really the responsibility of the cruelties practiced by the ancien regime. At the same time, Shelley warns of the dangers she sensed in the kinds of rational experiments with traditional family structures that her own radical circle practiced. Frankenstein is also an implicitly conservative defence of domesticity.

- Anne K. Mellor, ‘Making a Monster’ in Esther Schor, ed., The Cambridge Companion to Mary Shelley (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003). Available in print and as eBook.

In this collection of specially commissioned essays, well-known scholars review Mary Shelley 's work in several contexts (literary history, aesthetic and literary culture, the legacies of her parents) and also analyse her most famous work-- Frankenstein. The contributors also examine Shelley as a biographer, cultural critic, and travel writer. The text is supplemented by a chronology, guide to further reading and select filmography.

In her wide-ranging essay, ‘Making a Monster’, feminist critic Anne K. Mellor, reviews the main accounts of how the 18-year-old Mary Shelley came to write her book. She discusses Ellen Moer’s claim that the novel reflects Shelley’s own anxieties about childbearing and suggests that the book also reflects the painful pressure she felt to become an author like her parents and husband. Moers also reviews critics who read the Gothic genre in terms of a resistance to ‘compulsory heterosexuality’. Many of those who wrote Gothic novels in Shelley’s day were either homosexual men (Horace Walpole, Matthew Lewis, William Beckford, Robert Maturin), or heterosexual women (Anne Radcliffe, Charlotte Dacre, Emily Brontë) who were critical of traditional reductions of sexual desire to predatory masculinity and passive femininity. Shelley’s feminist critique of science is also given coverage, as is the idea that Victor and his creation are doubles of each other. Mellor also gives a detailed account of the revisions Percy Bysshe Shelley made to the novel for the second edition.

Web links

- Melvyn Bragg and guests discuss what inspired the 18th century anti-enlightenment Gothic movement

- The National Theatre production of Nick Dear's play, Frankenstein

- Guardian review of the NT production of Frankenstein

- Ruth Godwin suggests Frankenstein is about Mary Shelley’s experience of motherhood

- Eric Sonstroem’s FranknMoo project, an interactive digital learning environment which has lots of ideas for teaching the novel in innovative ways

- The British Library's Discovering literature page on Frankenstein