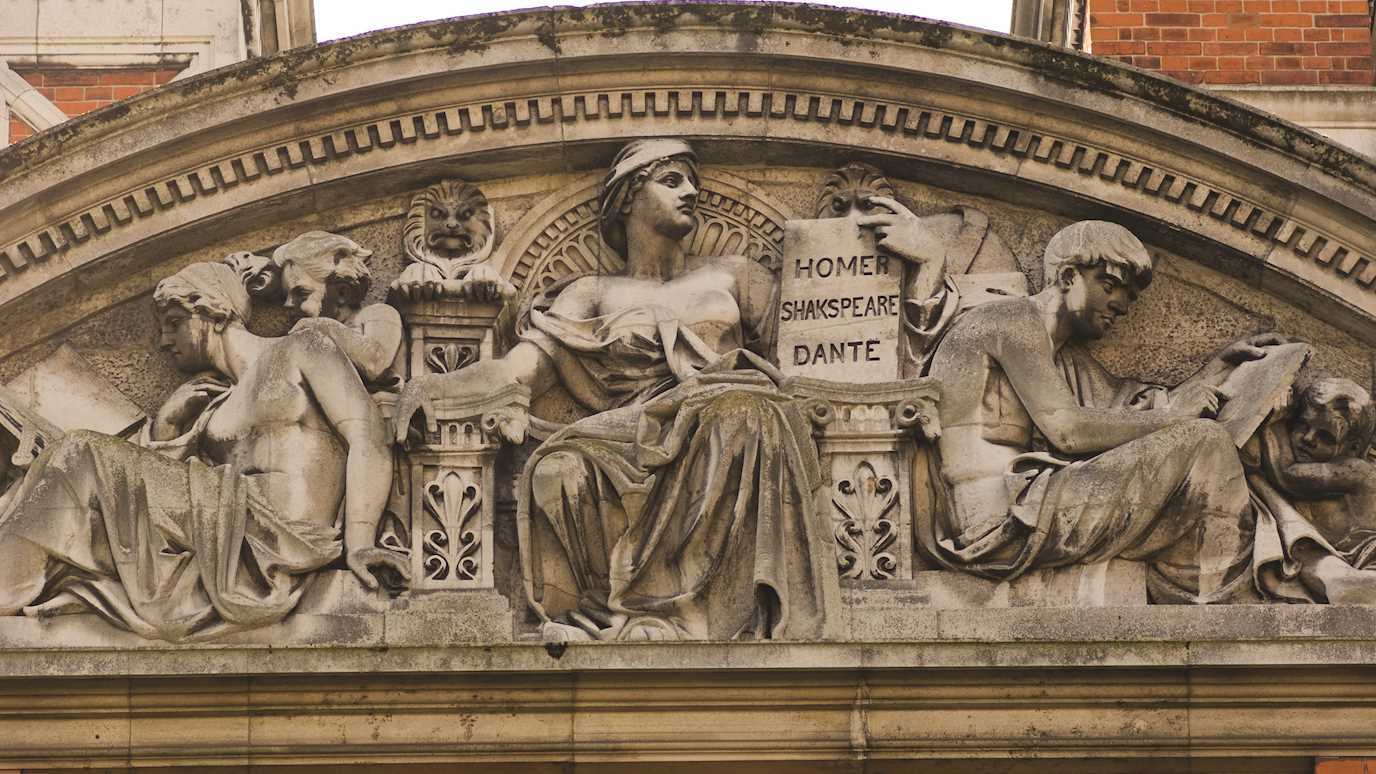

Dan Rebellato, Professor of Contemporary Theatre in the Department of Drama, Theatre & Dance at Royal Holloway, has written an audio essay about the melancholy and promise of an empty theatre.

In Spring 2020, all the theatres were forced to close. One of my favourite theatres in Britain is the Royal Lyceum in Edinburgh, a grand nineteenth-century playhouse that seats just over 650 but feels like it seats even more. I’ve seen some great shows there and when my friend the playwright David Greig became artistic director of the theatre four years ago, I watched with pleasure as he turned it into one of the most exciting theatre programmes in the country. When everything shut down in the Spring, David asked several theatre makers if they would write a letter to the Lyceum, to keep going the link between the silent theatre and its absent audience. This is mine, read by the wonderful theatre maker Emma Frankland.

Dear Lyceum

I’m looking at a painting on my computer. It’s by the British artist Henry Wallis and it was painted in 1853. It shows a domestic interior; it’s a bare, undistinguished room; the floorboards are ill-fitting and rough; the plastering is uneven and yellowed with limewash; there’s a huge fireplace jutting into the picture on the left, some assorted wooden chairs around the walls and a writing desk pushed up against a wide mullioned window looking out on a hazy landscape.

Henry Wallis The Room in Which Shakespeare Was Born (1853) Photo © Tate. Image used under Creative Commons license CC-BY-NC-ND 3.0 (Unported)

The painting looks like a stage set. The picture frame is a proscenium showing us an empty stage, waiting for actors to occupy it. This may be deliberate, because the painting is called ‘The Room in Which Shakespeare Was Born’.

Henry Wallis was a Pre-Raphaelite and you can trace that in the painting’s mixture of modern vividness and misty historical reconstruction, its investigation of mysteries of creativity, genius, and origin. The Pre-Raphaelites were drawn to Shakespeare’s characters and, here, to Shakespeare himself, whom they reconstruct as a kind of mystical romantic, lucid and elusive, old and timeless, ordinary and unique, common and singular.

Despite its near-photographic fidelity, the painting is full of paradox. The painting gains its entire drama from the presence of Shakespeare who is absent from the painting. Without Shakespeare, it’s just a room, but Shakespeare’s not there, so it is just a room? Wallis was painting well into the nineteenth-century rediscovery of Shakespeare and the supposed gap between his humble origins and the greatness of his writing; the more the genius was praised the more baffling his origins seemed, a mental strain that ends up in the silly quest for the real author of his plays.

But the clumsy phraseology of the title ‘The Room in Which Shakespeare Was Born’ (not ‘Shakespeare’s birthplace’ or ‘The Birth of Shakespeare’) also displaces the image in time. Are we looking at the room in which Shakespeare was born now? Is this the room shortly after he was born? Is this the room in which Shakespeare was born, before he was born? The writing desk contains an apparent manuscript: what are we to make of that? The room was on the second floor of the Shakespeare family’s home on Henley Street in Stratford-upon-Avon, but Shakespeare is only thought to have lived there as a child; the manuscript isn’t his. Is the manuscript indicative of the literary atmosphere into which Shakespeare was born? Or is it a present-day image of what Shakespeare brought into that world? Did the manuscript create Shakespeare or did Shakespeare create the manuscript?

The reason I’m telling you this, Lyceum, is that it bears on the melancholy puzzle of the empty theatre.

What is an empty theatre? It’s nothing and it’s everything.

As I write the Premier League is considering playing matches behind closed doors. It’s not going to be ideal but it’s just about possible because a football match has a functional outcome: a score. We couldn’t play plays behind closed doors, because they have no outcome; they are just what they are and if they are not seen they are nothing.

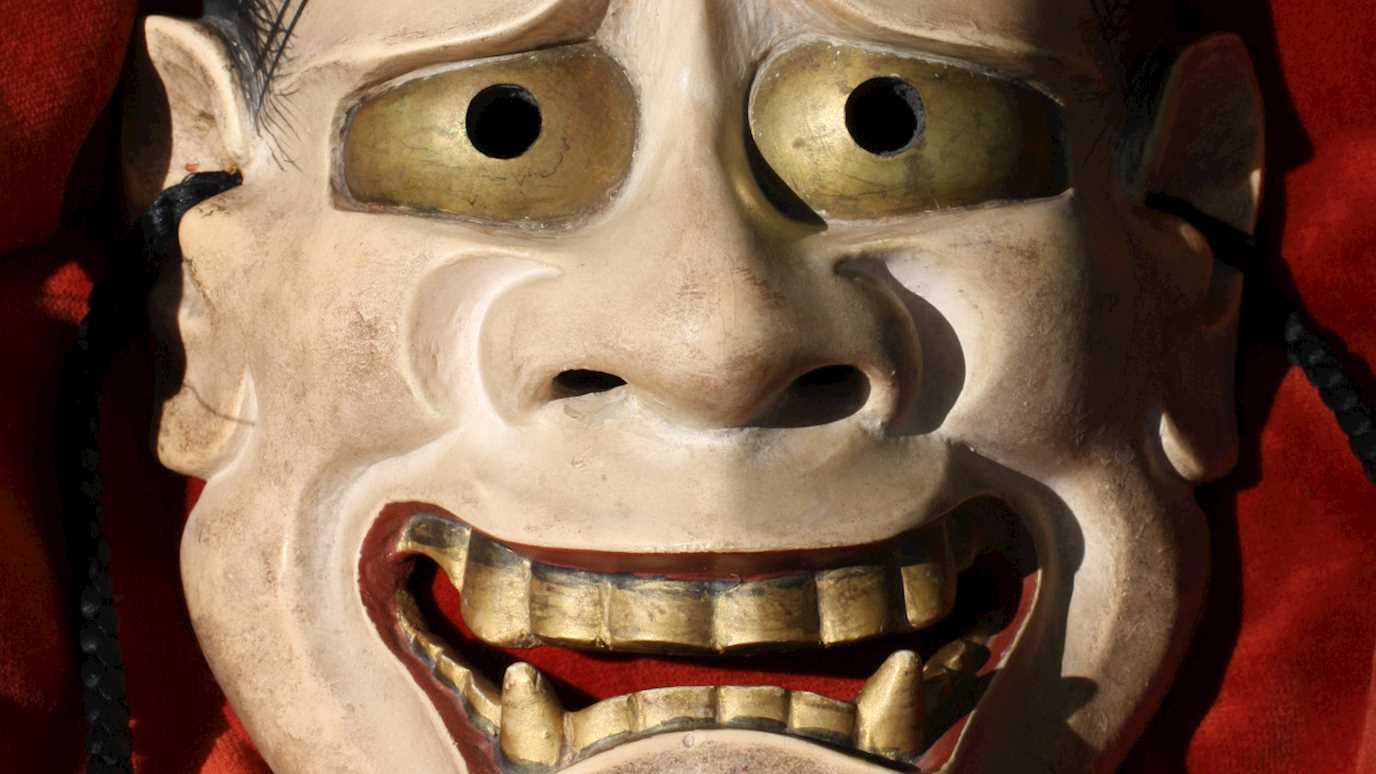

There’s another art project I think about when I think about empty theatres and that is the photograph series created by Tim Etchells and Hugo Glendinning, called Empty Stages which started in 2003 and is still going on.

Mini Theatre Ljubljana Castle, Ljubljana Slovenia from the Empty Stages project by Tim Etchells and Hugo Glendinning (2003-present). Photo © Hugo Glendinning.

It’s a series of photographs of exactly what it sounds like: empty stages. These are stages in church halls and civic centres, working men’s clubs and pubs. Sometimes there are scraps of performance visible: musical instruments set up for a performance, ladders, a glitter curtain. The images have a kind of joy and a kind of melancholy; they are gaudy and subdued; absurd and poignant.

I think it’s because, like Henry Wallis’s painting, these photos of empty stages put time out of joint. Are these stages empty because the performance is finished, the audience has gone, the Elvis impersonator has left the building? Or are these stages empty because the performers are getting into costume, the crowd are gathering in the bar, and the stage is pregnant with possibility?

I want you to know, Lyceum, that we want to meet our friends in your glass atrium, that we want to gather in your beautiful round bar, and we want that itch of expectation as you tell us that the theatre is now open and we take up our seats knowing that everything is possible.

One of the most famous statements about theatre by any British theatre maker of the last hundred years is about an empty theatre. In 1968, the director Peter Brook wrote ‘I can take any empty space and call it a bare stage. A man walks across this empty space whilst someone else is watching him, and this is all that is needed for an act of theatre to be engaged’. He means that it takes very little to turn an empty theatre into one that is full.

Right now, a man (or woman) is not permitted to walk across an empty space while someone else is watching them. I hope you know, Lyceum, that your empty building is full of our hopes and wishes; we can’t wait to see you again. But for now, all we can do is imagine ourselves into your spaces. Your wide side aisles. Your shabby splendour. Your genteel magnificence. Your soaring proscenium. Your whiplash balconies. Your sweeping staircases. And your deep, broad, high stage on which we imagine a single actor walking across your empty stage and filling it with possibility.

We love you, Lyceum. See you soon.

Dan

Link to audio recording