The Department’s Professor Dan Rebellato has translated and adapted the nineteenth-century classic play Lorenzaccio by Alfred de Musset for BBC Radio 3 and it goes out on Sunday 10 March at 7.30pm.

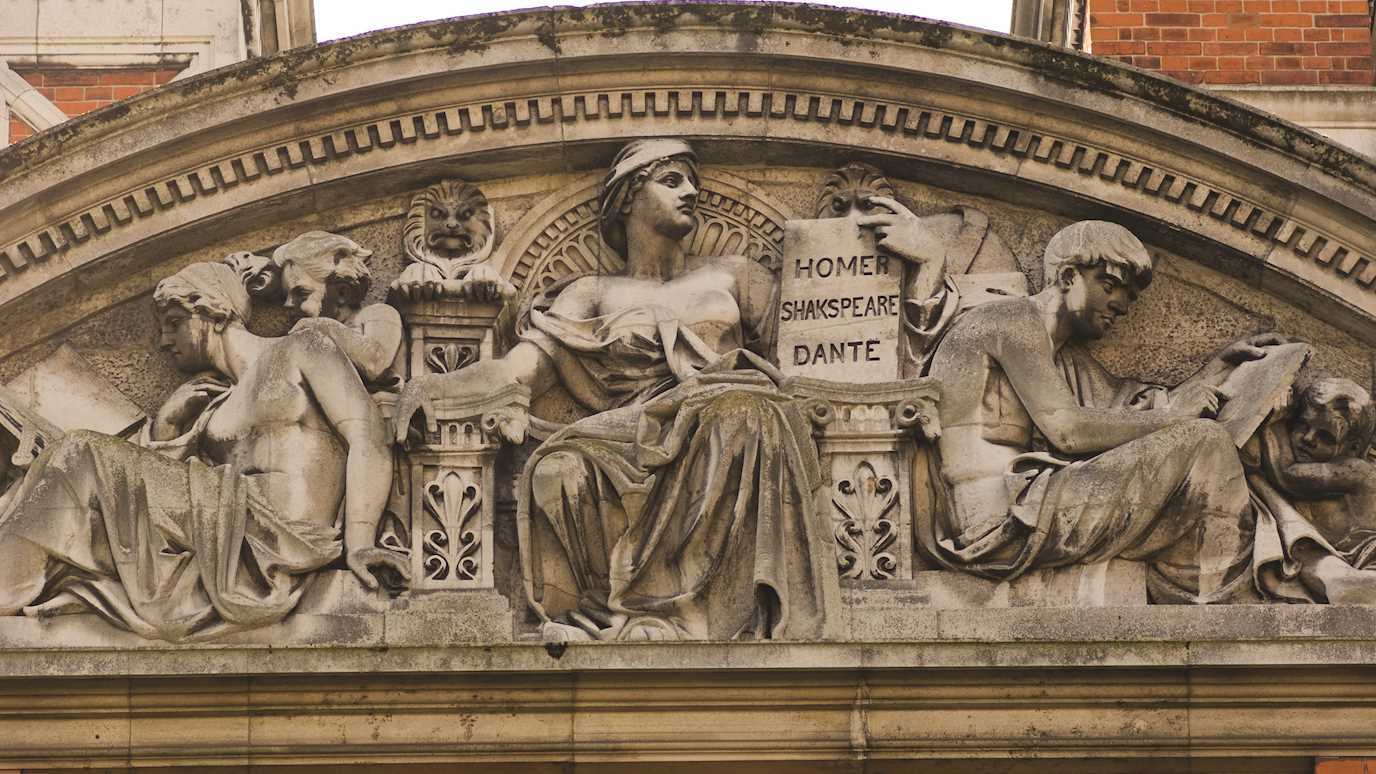

Segment of Alphonse Mucha's poster for Lorenzaccio (1896)

The play is set in the corrupt Florentine court of the Medici in the 1530s and focuses on Lorenzo de Medici who has entered the court supposedly to bring down the tyrannical Duke Alexander – but has he been corrupted himself? Lorenzaccio is a panoramic thriller that asks: what can good people do in evil times?

‘I first read the play as an undergraduate thirty years ago and I fell in love with the play immediately,’ says Dan. ‘But the strange thing is that if you ask someone in France whether they know Lorenzaccio, they’ll look at you like you’ve asked if they’ve ever heard of King Lear: it’s one of the great plays of the French dramatic repertoire; but in this country it’s almost unknown. I’ve mentioned it to directors, actors, playwrights and theatre academics and rarely has anyone heard of it, let alone read it.’

It’s quite a challenge to adapt this play. The original is probably getting on for five hours’ long and the Sunday night slot on Radio 3 is maximum 90 minutes. ‘It’s involved really getting under the skin of the play, understanding its mechanics, to find a clear line through the play, without sacrificing some of the play’s epic sprawl,’ Dan explains.

‘Also, Musset wrote the play in 1834 and, though it was set in the sixteenth century, it was clearly a play about the July revolution and the Republican political project of the 1830s. I wanted to find a way to reflect that contemporaneity. I’ve worked with Polly Thomas and Eloise Whitmore [the director and sound designer respectively] so often and we make a great collaborative team. With this project, we also thought it would be good to keep the language and the references in the 1530s but create a sound world that is entirely 2019. The results are, I hope, to give everyone not just a vivid introduction to Musset’s play but also to sense the uncanny political intervention of the play.’