In the archives of Royal Holloway, 2000 year old documents shed light on the lives of women in Roman Egypt.

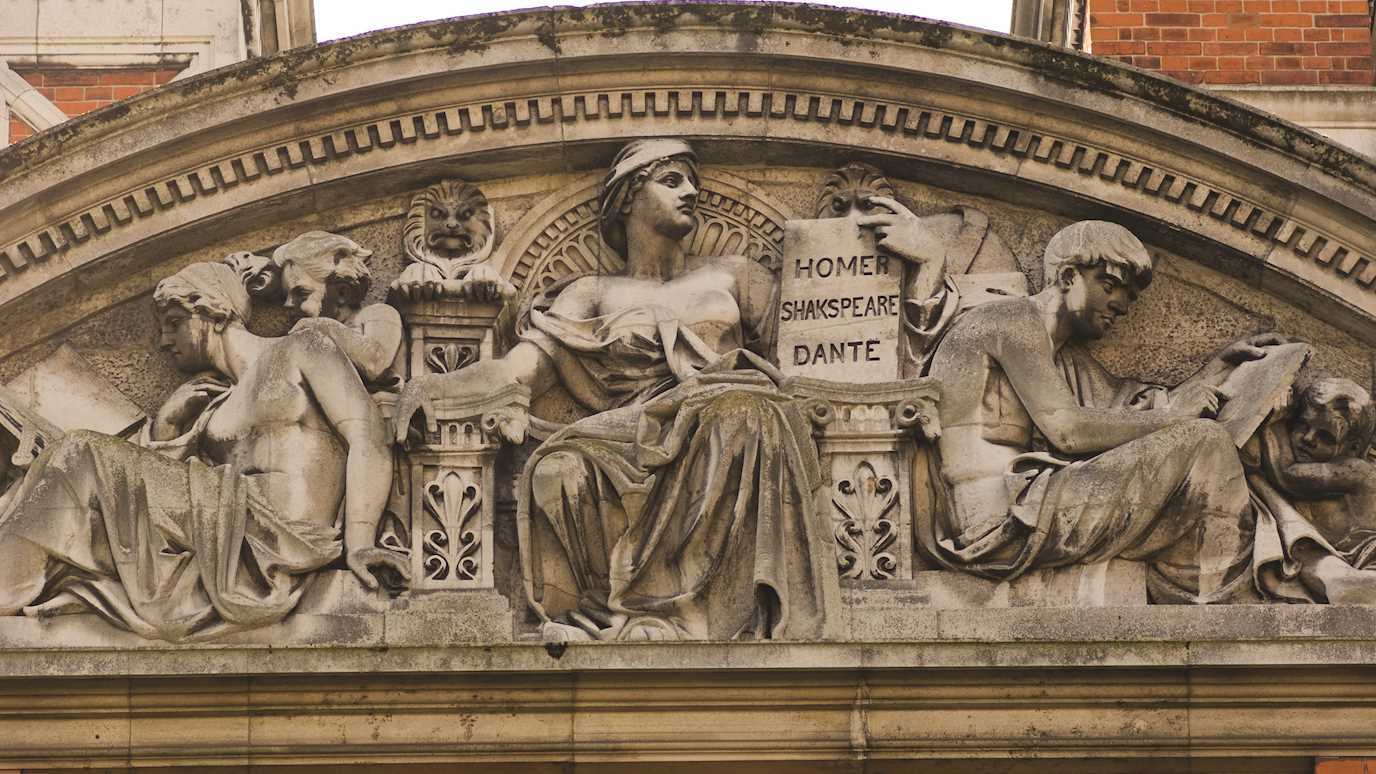

Over a century ago, two young Classicists, Arthur Hunt and Bernard Grenfell, travelled to Egypt on the trail of unconventional treasures, papyri, ancient papers, preserved in the desert sands. For nearly two centuries scholars had been aware that there were potentially new Classical texts to be discovered in Egypt but it was only in the last years of the nineteenth century that the academic world began to take investigate. Grenfell and Hunt were out to rediscover the Classical tradition: a new Renaissance beckoned.

They set up camp at al-Bahnasa (ancient Oxyrhynchus) in 1898 and struck paper. Thousands of texts were unearthed and in their first year found a fragment of an early uncanonical and lost gospel. The stir created by the discovery of an alternative Christian tradition was such that its publication paid for the next years’ excavations.

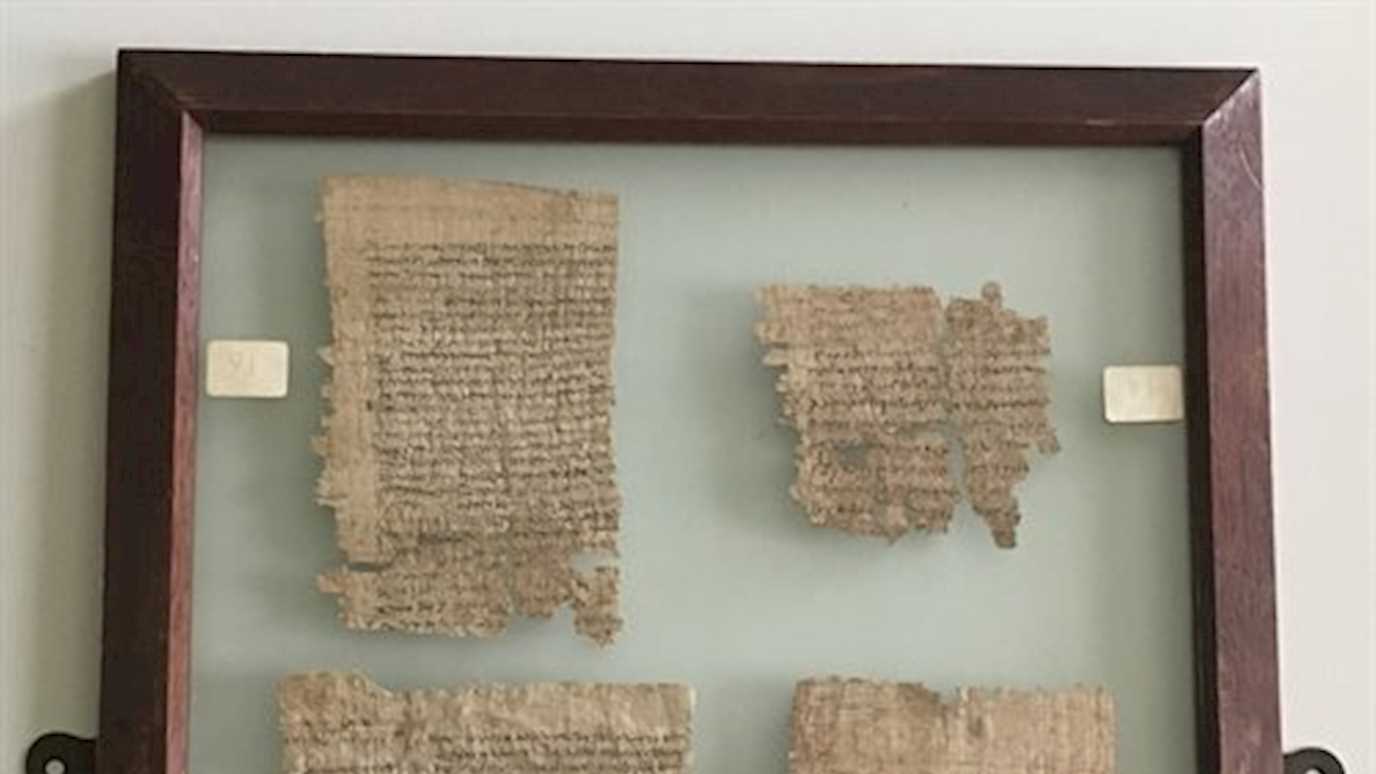

Most of the Oxyrhynchus documents were deposited in Oxford, but Hunt distributed some texts to other learned institutions. In 1900, Royal Holloway College thus obtained three complete documentary texts and a number of fragments.

The first text is in two sections, top left and right on the photograph. It is a late second-century AD text:

Chosion of Sarapion of Harpokration, mother Sarapias, from Oxyrhynchos, greetings to Tanenteris, daughter of Thonis, son of Thonis, of the same city. I agree that I have received from you through Heliodoros and associates, managers of the bank near the temple of Serapis at Oxyrhynchus, 400 silver drachmae, being for the food, clothing, oil and other expenses for the two years my slave Sarapias nursed your daughter Helene… (P.Oxy. 1 91 AD 187)

In the second fragment, about four lines down, the handwriting changes. At this point, the document prepared by the scribe ends and Chosion acknowledges that he has received the money in his own handwriting.

The second text is at the bottom left side. Someone in antiquity had pasted this text together with at least four others. The main text is from the second century and relates to the sale of a slave woman, Dioskorous, aged 25. She had belonged to a citizen of Alexandria but was now being sold to her third male owner, Julius Germanus, a Roman, for 1,200 drachmae (P.Oxy. 1 95 AD 129).

The third text, on the bottom right, is the earliest, dating from the first century AD:

To Herakleides, priest, chief justice, superintendant of the chremistae (judges, normally used in civil cases) and the other judges, from Syra of Theon. I went to live with Sarapion, bringing with me a dowry of 200 drachmae. I took him into the house of my parents since he was without means and I conducted myself blamelessly. But Sarapion spent my dowry without consulting me, insulted me, ill-treated me and used violence against me, depriving me of the necessities of life. Finally, he left me without resources. I beg you, therefore, that you order that he be brought before you and forced to repay my dowry plus half again.. (P.Oxy. 2 281 AD 20-50)

Hunt did not select these texts at random. He chose the texts to educate the young women of Royal Holloway College about their lives of their predecessors 1600 years earlier. More than six decades before women’s history emerged into the mainstream, we see a premonition of its appearance.