Royal Holloway researchers are part of an international and Saudi Arabian team who have discovered that over the last 400,000 years, multiple pulses of increased rainfall transformed the usually arid Arabian Peninsula into a hospitable route for human population movements across South West Asia.

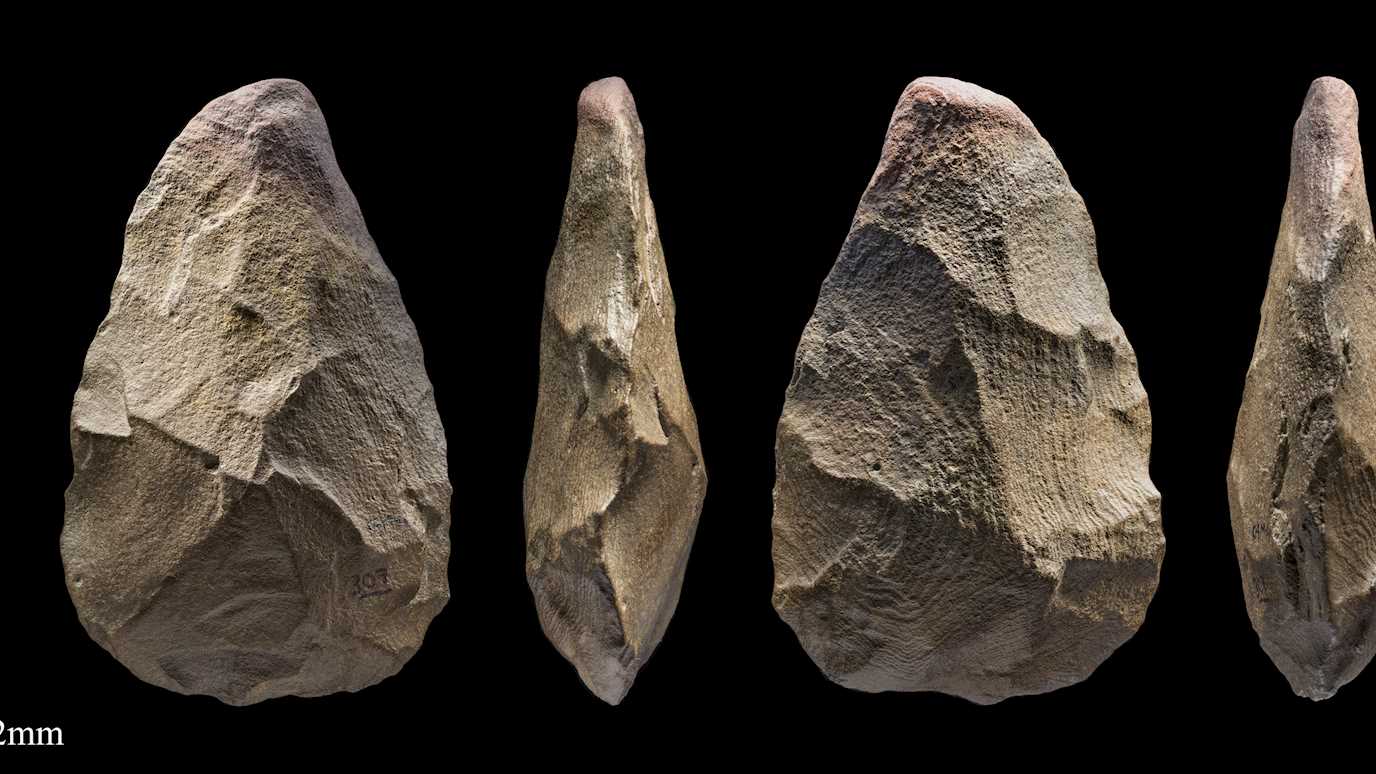

A 400,000 year ‘handaxe’ stone tool from Khall Amayshan 4. Photo credit: Palaeodeserts Project (photo by Ian Cartwright).

Dr Richard Clark-Wilson, along with Professors Simon Armitage, Simon Blockley and Ian Candy from the Department of Geography at Royal Holloway were involved in the analysis of the sediments that provide the evidence for these wet phases. Stone tool assemblages that indicate the presence of early humans in the region are intimately associated with these sediments providing the link between early humans and intervals of increased rainfall.

The Royal Holloway team determined the age of these wet phases using luminescence dating –a technique that records the length of time since tiny grains of sediment, typically sand, were last exposed to sunlight - showing that each occupation dates to a time when rainfall is known to have increased in the region.

The new research carried out in the Nefud Desert of Saudi Arabia was in collaboration with scientists at the Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History in Jena, Germany and the Heritage Commission of the Saudi Ministry of Culture, as well as other Saudi and international researchers.

The researchers also discovered thousands of stone tools that reveal multiple waves of human occupation and shows changing human culture over time. Along with the oldest dated evidence for humans in Arabia at 400,000 years ago, these new discoveries are described as a “breakthrough in Arabian archaeology” by Dr Huw Groucutt, lead author of the study and head of the ‘Extreme Events’ Max Planck Research Group in Jena, Germany, based at the Max Planck Institute for Chemical Ecology.

Professor Simon Blockley from Royal Holloway, said: “This work shows the important role climate change made in human adaptation, even in the early history of our species.”

Professor Ian Candy from Royal Holloway, continued: “Along with my colleagues, we were able to date the sediments and found that within a dominant pattern of aridity, occasional short phases of increased rainfall led to the formation of hundreds of lake, wetlands and rivers that crossed most of Arabia, forming key migration routes for humans and animals such as hippos.”

Unlike bones and other organic materials, stone tools preserve very easily, and their character is largely influenced by learned cultural behaviours. As a result, they illuminate the background of their makers and show how cultures developed along their own unique trajectories in different areas.

Each phase of human occupation in northern Arabia shows a distinct kind of material culture, suggesting that populations arrived in the area from multiple directions and source areas. This diversity sheds unique light on the extent of cultural differences in Southwest Asia during this time and indicates strongly sub-divided populations.

Professor Simon Armitage, from Royal Holloway, who led the luminescence dating work, explained: “Luminescence dating is one of just a handful of techniques that allows us to reliably constrain the timing of sediment deposition and the age of the associated archaeology this far back in time. It is particularly well-suited to the study of desert regions because of the abundance of sand rich deposits. It has been fundamental to our understanding of human dispersal”.

Dr Huw Groucutt, said: “Arabia has long been seen as empty place throughout the past. Our work shows that we still know so little about human evolution in vast areas of the world and highlights the fact that many surprises are still out there.”

Professor Michael Petraglia, from the Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History, concluded: “It’s remarkable; every time it was wet, people were there. This work puts Arabia on the global map for human prehistory.”