Work carried out by academics from three leading universities, including Royal Holloway, University of London, sets out a plan to end the ‘reading wars,’ the debate about how best to teach children to read which has divided, teachers, parents and politicians for decades.

Ending the reading wars could improve literacy

The debate has been between those who champion using a phonics led approach, in which children are taught the sounds that letters make, and those who support a ‘whole-language’ approach, focusing on children discovering meaning in a literacy-rich environment.

In a paper published today in the journal Psychological Science in the Public Interest the authors examine data from more than 300 studies and reports published from 1955 to 2018. The evidence shows that both approaches have value, but there is a need for an ongoing reading curriculum through primary school and into high school.

The research team, Kathy Rastle, Royal Holloway, University of London, Kate Nation, University of Oxford and Anne Castles, Macquarie University, Sydney, Australia, have reviewed the past 60 years of research in order to enable it to be more readily used in schools.

Professor Rastle said: “We hope that policy makers and teachers will agree that to ensure more children leave school with high literacy skills requires a longer term reading agenda which will enable children to build the text experience necessary to become confident, skilled readers.”

Professor Nation added: “We decided to bring this knowledge together in one place to provide an accessible overview. We didn’t want it to be buried in scientific literature, we wanted it to be useful to teachers.”

In the past, similar research has sometimes been slow to make inroads into the classroom. This has left literacy problems at a worryingly high level, despite general recognition that literacy is a vital skill and teaching children to read is one of the most effective way of reducing disadvantage in society.

Professor Rastle said: “Phonics doesn’t block developing an enjoyment of reading, it enables it. Our conclusion is that phonics is necessary but not sufficient on its own. It is the foundation of what comes after and what comes after is very important.

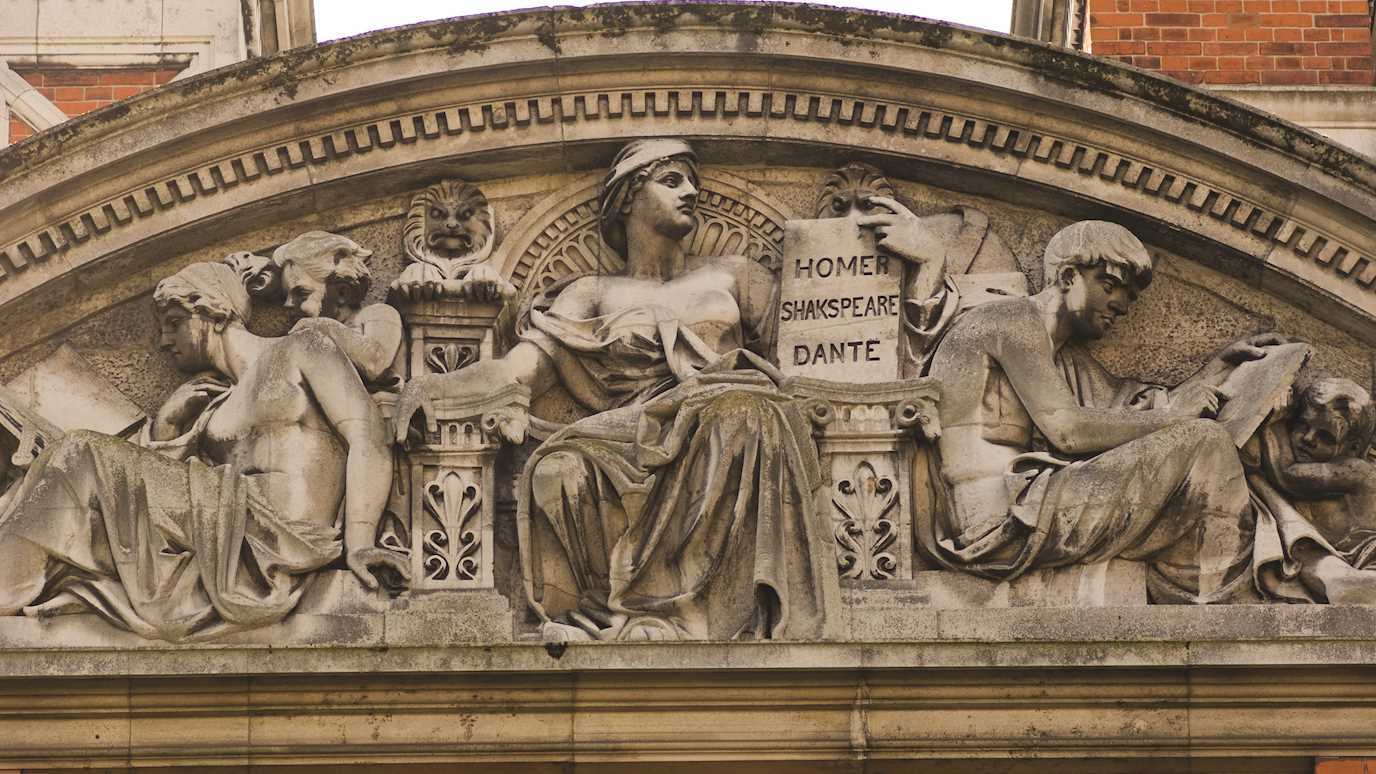

“Teaching of reading needs to be informed by both a deep understanding of language and writing systems. Writing is a code for spoken language, and children need to be taught how to crack that code,” added Professor Rastle.

As Professor Castles explains, “In English, there’s no systematic mapping between a written word and its meaning, but there is a systematic mapping between a word and its spoken form. The phonics case falls naturally out of this: written language is a code for the spoken form and so it makes sense to give kids the code.”

The researchers say that the challenge is to help teachers take advantage of research findings about how young readers learn to crack the code, and to share this knowledge in a way that will lead to better outcomes for children.